Mack in the Saddle Mack in the Saddle

Tests revealed that Iowa State professor Barbara

Mack had ticking 'time bomb' in her head. here's why her life is back to

normal just a month after brain surgery.

by Dawn Sagario

Register Staff Writer

Barbara Mack pads barefoot through her kitchen to answer the door on

a morning in July, dressed in a black T-shirt and blue shorts. Her

booming "Come on in" greets you, her voice and chatter strong

as she leads the way into the solarium.

She eases into a cushy chair, slouching into it to get

comfortable. She runs her fingers -- her nails pink with polish --

through her reddish-brown hair, occasionally leaning down to pet her tow

cats, Why Not and Mizewell, who have decided to keep her company in the

room.

Mack, 52, is an Iowa State University journalism professor and

former member of The Des Moines Register's legal team.

Two weeks prior, she was a brain surgery patient at the

University of Iowa, being treated for an aneurysm discovered in May. Dr.

John Chaloupka placed tiny platinum coils that now sit in the tiny bulge

in a vessel in her brain, in the hopes of preventing it from rupturing.

But you would be hard pressed to tell she is gone through such

delicate surgery, listening to her animated voice and zealous

storytelling. A strange feeling

It was 4 p.m., March 24, when a visit from a friend would later

turn into what Mack calls a "blessing in disguise."

The two were sitting in Mack's home in Des Moines when Mack said,

"Something just happened. I just feel like I a taste of Chinese

mustard."

Mack recalls no pain. But she didn't feel well, either.

"I didn't know what I was experiencing. It was like eating a

big wasabi, where you think, "Whoo! That opens your sinuses."

She chose not to go to the hospital.

Mack thought it may be a recurrence of a severe viral infection

of the inner ear had suffered earlier in the year, following knee

surgery. She called her ear, nose and throat doctor, who told her to

come in for an MRI on May 5.

A week later, on May 12, Mack found out that she had had a very

mild stroke -- a 2 or 3 on a scale of 1 to 10, she said. She counts

herself lucky to be alive -- both of her parents and many relatives had

died of strokes.

Then Mack recalls, the neurologist said, "We found something

else."

Mack remembers cursing in her head.

"We found an aneurysm," the doctor said. He wanted Mack

to see a local neurosurgeon. Five days later she was discussing her

options with a Des Moines doctor who explained three possibilities:

- They could just watch the aneurysm, which was 5 millimeters in

size, and check back with her in six months.

- The aneurysm could also be "clipped," which would entail

removing a section of the scull. The surgeon would then place a tiny

metal clip across the "neck" of the aneurysm, to stop

blood from flowing into it.

- The third option was to have the aneurysm "coiled,"

using a small microcatheter threaded from the groin all the way up

to the brain. Tiny platinum coils would be deployed into the

aneurysm through the microcatheter, which are supposed to help

prevent blood flow to the aneurysm.

The Des Moines neurosurgeon was ready to go ahead with the clipping

procedure. Mack was not.

"Nobody gets to crack open my head and go rootin' around

until I get a second opinion," she said.

She decided to meet with Dr. John Chaloupka, a "coiler"

at the University of Iowa. Making a decision

Like any good journalist working on a big project, Mack did her

research. From May 17 to June 8, the date of her meeting with Chaloupka,

Mack studied brain aneurysms for more than 100 hours. She read Web sites

like brainaneurysm.com. She interviewed clippers and coilers in Arizona,

and at Massachusetts General Hospital, University of California, San

Francisco, and University of California, Los Angeles.

"You realize how important it is to be a knowledgeable

patient," Mack said, "You can't depend on one doctor, and you

have to ask a lot of questions."

Time and time again, Mack came across both doctors and past

patients who praised Chaloupka's work.

"Oddly enough, everybody, every doctor, out of state that I

talked to said first of all, they knew this guy, and second said, 'Well,

if you're in Iowa, why isn't John Chaloupka doing this?' "

One definite plus with brain coiling was the downtime. Mack

expected to be home several days after brain coiling surgery.

After a two-hour visit with Chaloupka, Mack was impressed with

his honesty, candor and patience in answering her questions. She said

she also had a good feeling about the staff he worked with.

Her operation was set for July 12 at the University of Iowa. A

stent would also need to be placed into the blood vessel, to help

prevent the coils from dislodging once they were placed in the aneurysm.

"You get a clear sense that they feel confident in each

other," Mack said. "And I was so impressed I was willing to

put my life in his hands."

She said she doesn't fear death so much as she does losing the

core of who she is.

"My fear is the loss of everything that makes me, me. My

greatest fear is spending my life lying inside a nursing home, drooling

out the side of my mouth. The world comes to Iowa

Aneurysm patients from around the United States and the globe --

including Canada, Mexico, Ireland and Israel -- have come to be treated

by Dr. John Chaloupka.

"We have an internationally recognized service here for

treating aneurysms. we're world-acclaimed for doing this,: said

Chaloupka, who began his career in Iowa in late 1998, when he traded his

New England practice for a new life in the Midwest.

Leaving behind his job in New Haven, Conn., as director of the

international neuroradiology service at Yale University's School of

Medicine, he came to Iowa City to take the helm of a similar program at

the University of Iowa.

When he first arrived at the U of I, about 20 aneurysm cases were

being treated a year. Chaloupka said. In the past seven years, he has

performed nearly 600 aneurysm surgeries. by next year, he predicts

hitting the 1,000 mark.

More than 170 cases are now treated annually, with three to four

aneurysm surgeries performed weekly, Chaloupka said. About 85

percent of the aneurysms are being coiled, up considerably from seven

years ago, when about 20 percent of patients had brain coiling done.

As a fellow at UCLA in 1991, Chaloupka, was at the forefront of

brain coiling as one of the first physicians to perform the procedure.

Then, he said, doctors were working with limited selection of coils,

catheters and other devices, restricting those eligible to a small

subset of patients, which included individuals with no other options.

Since then, brain-coiling technology and technique has rapidly

evolved and improved within the last decade, making it available to a

broader population of XXX problems

compared with the non-invasive procedure. And the creation of newer

coils that more rapidly help the growth of scar tissue in the aneurysm

have helped to prevent ruptures.

but he cautions, "there are some aneurysms that just can't

be coiled," which include those that are blood clots in the brain.

For Mack's surgery, Chaloupka used a new type of coil called a

"pop-up" coil, which did not require the stent that he

initially thought was needed in Mack's surgery.

"We didn't need to do it. And I think that's a good

thing," he said. "The stent is an extra intervention and

theoretically, that adds a little more risk to the operation." He

added that patients who have stents put in also have to take aspirin and

Plavix, a medication that helps prevent blood clots, for three months.

XXX about 9 a.m.

The next day Mack was up and walking. She took a shower, got

dressed and asked a nurse if she could go for a "little walk"

with her husband, Jim Giles.

Their walk, across the campus of the University of Iowa, was

between a half a mile to a mile long.

When they returned, Mack said, the nurse was surprised. "She

said 'Oh, I thought you were going down the hall.' ".

The day after that, Mack was released from the hospital. Later

that night in Des Moines, Mack, her sister and husband, had dinner at

Latin King. Ten days following the procedure, she was giving a two-hour

presentation to city clerks on dealing with the media.

Two weeks after surgery, Mack was lounging in her sunroom.

"It's amazing. Everything has been better than expected," said

Mack, XXX

State.

She gushes about the kindness and thoughtfulness of those close

to her. She raves about her doctor.

"I came to the conclusion -- I think this guy is just that

good," she said of Chaloupka. "I think he's a top gun."

The only outward physical signs of Mack's surgery were two

bruises -- one, the size of a 50-cent piece, marked the entry site where

the catheter was inserted. Other brain-coiling patients have reported

bruises the size of saucers, Mack said.

Mack had also read the experiences of other brain-coiling

patients who told horrific tales of severe headaches following the

surgery. She has not had any.

Now she drives, goes to the grocery store, attends water aerobics

class, and goes for walks as often as she pleases. Any heavy lifting,

though, is out.

"Basically I'm trying to cut myself enough slack to make

sure I get plenty of rest," said Mack, who plans to return to

teaching for the fall semester at Iowa State.

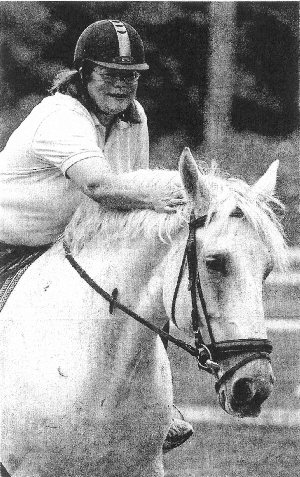

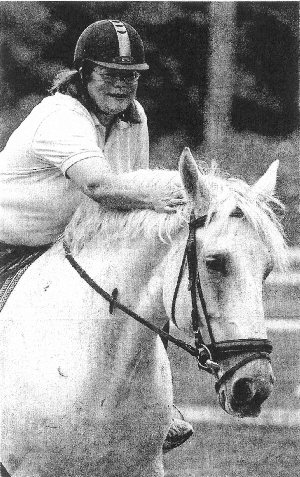

While she couldn't ride her horse, Mikki, she still made visits

to the stables to play with her.

"Oh God, I miss her so much. I miss riding," lamented

Mack, who has been sidelined essentially all year doe to knee surgeries,

illness, her stroke and brain aneurysm operation. "This is the

longest in my adult life that I've gone without being on a horse."

Chaloupka said no riding for a month to six weeks, post-surgery

-- provided there would be no jumping or galloping.

Mack agreed. So about one month after brain surgery, on July 11,

she was back in the saddle, taking Mikki for a ride at Valley Park

Stables in Des Moines.

While her rapid recovery with few complications has bee a welcome

surprise, it has been tempered by other post-surgery news. During the

procedure, doctors also found atherosclerosis (the build of plaque in

the artery walls) in the back of her brain.

"This has bee a great wake-up call for me to clean up my

life," she said. "I ate Smart Balance on my whole wheat toast

this morning. ...(I have to) get the cholesterol down, control the blood

pressure, weight loss, all that good stuff."

It's been a tough year. But the bout with her brain aneurysm, in

particular, has been "humbling."

"I'm healthier now than I have

|

Mack in the Saddle

Mack in the Saddle