Jungling, 1895

Chapter 5

There was a large river flowing through the city, which Curly said was the Ohio. We did not look for the jungles, but located a cheap rooming house where Curly engaged a room for the week and introduced me as his son. The room contained a couple of old cane-seated chairs, a dilapidated dresser, a commode with a large china basin and pitcher, and a wooden bed with the usual "donicker" (chamberpot) beneath it. A flight of rickety stairs led down to a large privy in the back yard. Above the central door of the privy swung a white sign, upon which was printed in large black letters an admonitory "Don't .... .. ... ....". The inner whitewashed walls were covered with the usual backhouse poets' effluvia.

We ate what we could of the remainder of our lump, and fed the rest to a large black Newfoundland dog whose name, by coincidence, was "Curly". After our meal, Curly told me to remain in the room while he went to the postoffice. He returned in about an hour with a small package which he opened on the bed. It contained several smaller packets, which upon being opened caused me great wonderment. There were several dozen plain and gem-studded rings,several brooches, and three fine-looking watches. He laughed at my amazement and told me they were "phoney". He said that he had ordered them by mail from Chicago at a total cost of about five dollars, and that he expected to sell them for about two hundred. in fact, he received considerably more.

He sold one of the "diamond" rings that same night to a negro preacher who was conducting a revival meeting nearby. His story was that his wife had died and that the bauble had been her engagement ring. However, the usual story was to make the buyer believe that the property had been stolen. This left no comeback for the buyer, for if he complained to the police they would either laugh at him or scold him for buying "stolen" property.

We both enjoyed the antics of the revivalists that evening as we sat on a rear bench near the entrance to a large tent where the meetings were held. The minister's exhortations must have carried conviction to the several hundred listeners, for when the collection plates were passed almost everyone dropped a coin or two into them. The plates were so heavy with coins that before the two collectors had completed their job, they had to use both hands to keep the pan level. I wanted to leave, but Curly said he wanted to see the preacher. After the crowd had left, he led me by the hand to the platform where the preacher and his two assistants were counting the evening's take. Curly asked the preacher for a word in private, and the preacher asked his helpers to leave. When they had retired to the back of the tent Curly introduced me as his son, complimented the preacher on his eloquence, and began his spiel about the engagement ring. He offered to let him have the ring for fifty dollars, but the preacher was wary. He asked if the diamond would cut glass, and Curly assured him it would. The preacher handed the ring back with some remark about proving it, went to the rear of the tent, and returned with a small mirror. Curly drew the stone of the ring acoss one corner of the mirror and to my surprise, and probably the preacher's, the stone had made a plainly perceptible scratch. The preacher seemed satisfied and began to dicker. He offered twenty dollars, and Curly dropped to forty. The preacher raised his offer by degrees to twenty-five dollars while Curly came down to thirty. Finally Curly took me by the hand and turned to go, and the preacher capitulated. They sat down and began counting the evening's collection, which in dollars, half dollars and quarters alone amounted to a little more than twenty-five dollars. The preacher gave Curly twenty-five in silver, then opened his pocketbook and extracted a five-dollar greenback which he folded and placed in Curly's hand. He picked up the ring, stuck it in his purse, and with a "God bless you, brother" accompanied us to the tent's entrance and bade us a pleasant goodnight.

We found a small restaurant, had a good supper and went to our room. Curly emptied his pockets of the silver, tied it in a handkerchief, and slipped it under the mattress. He produced the five-dollar bill, unfolded it, scrutinized it carefully, and burst out laughing. It was a five-dollar bill, alright, but Confederate money, worth about ten cents a thousand. I was indignant and wanted Curly to take it back and make the preacher exchange it for a good one, but he only smiled. He held the bill over the chimney of our kerosine lamp until it blazed, and lit a cigarette with it, after which we tumbled into bed.

The next day Curly hunted up likely-looking spots for me to work, rehearsed me in my spiel, and turned me loose. I was fearsome and nervous at first, but as one success followed another I gained confidence and by three o'clock that afternoon I had turned over to Curly, who collected after each contribution, nearly five dollars.

Apart from the day of the cornmeal episode, I averaged about six dollars for each day of about five hours' work. Curly worked the streets and saloons in the early evening hours with his phoney jewelry, and must have taken in at least twice as much as I. We moved to a more cheerful room in a better neighborhood at the end of the week, and ate at better restaurants. Curly bought me a new outfit of clothes, and got himself a new suit, shoes and hat. The hat was a J. B, Stetson felt, which no self-respecting tramp would be seen without if he could help it. The Stetson, I learned, was a badge of quality in trampdom, as it was for most railroad men at the time. Evenings we usually spent at home playing cribbage or casino, or at one of the several negro minstrel shows near the river. Saturdays, there was a baseball game; but as we were in Louisville for only four weeks, I saw only a couple of them. Begging was really a more exciting game to me; I had grown to like it.

Beginning the second week, Curly suggested that I try "panning" for a dollar instead of the usual fifty cents. I did so, but we soon abandoned it. My tears seemed to be able to extract fifty cents' worth of sympathy from my victims, but they went cold on the dollar. I think my first day netted only three dollars, and my second day two. On one of those days a young man, to whom I had told my sorrowful tale without apparent effect, passed on but came back a few minutes later as I was giving the "pan" to another man. He had a small crowbar with him. We pried up one of the two planks between which I had told him of dropping a dollar, and we all had a good search. There was such a mess of disintegrated horse manure, bits of paper, and other small trash that it was like looking for the proverbial needle. I found a large copper two-cent piece and the young man found a dime, which he pocketed. He replaced the plank and left, and I sat down on the sidewalk and began to sob. The other man stood watching me for a minute or two, and the fever of his sympathy finally rose to the dollar point. He slipped one into my hand, and with a comforting word or two went on his way. Curly, who had witnessed the whole affair, went into convulsions of laughter when I joined him a few minutes later, and we called it a day.

That night, Curly started on a spree. He came to the room about ten o'clock carrying a gallon jug and two quart bottles of whisky. He had had a few drinks, but was sober enough to instruct me how to care for him during his debauch, and begged me not to leave him alone when he was awake. He seemed confident that I wouldn't leave him; and he was right, for by now I simply adored him. He gave me a large roll of bills which he told me to hide. I was to keep the whisky for him to sober up on after he had consumed the contents of the jug, which he told me contained pure alcohol. I was to dilute this to half-strength with water and administer it to him when he asked for it. When the alcohol was gone, I was to give him the whisky in diminishing doses of about two ounces every two to three hours, and gradually increase the time between doses. I was to refuse to go out and buy more for him, and I was not to allow him to smoke unless I held the cigarette for him while he did so. As for food, he said he would want nothing. It was quite a burden to lay upon the shoulders of an eleven-year-old boy, but I resolved to do the best I could.

By midnight, the bottle of whisky was two-thirds gone and Curly was in a stupor. He had undressed and gotten into bed before becoming helpless, and before going to bed I poured out another drink for him and set it on the stand beside his bed. I turned the gas light down low and lay down beside him, but I couldn't go to sleep. I was frightened for fear of what might happen to him if I failed him in any way, and lay there sobbing my heart out. I must have dozed off, however, for it was getting daylight when Curly awoke and asked me for a drink. I gave him the one I had poured out and refilled the glass; but within a few minutes he asked me for another drink, which I gave him, refilling the glass with what remained in the bottle. I then got up, filled the whisky bottle half-full of alcohol from the jug, and aded an equal amount of water. By now it was daylight, so I got dressed and sat beside him on the bed, holding his hand and stroking it.

When he started on the alcohol he would take four or five drinks at intervals of about fifteen minutes, then fall asleep and sleep for three or four hours. During these sleeping periods I would go out and buy my meals, return with two or three dime novels, and read until he awoke with further demands for liquor. He had soiled the sheets, and I bribed the chambermaid to change them and wash his underwear. I washed his body myself.

This kept up for several days, and when the alcohol gave out I started to sober him up with the whisky. He could no longer hold the glass, and after a vain effort on my part to pour it into his mouth I borrowed a tablespoon and fed it to him in that way. He begged me for more than he had instructed me to give him, but I kept firmly to the formula he had prescribed. He once tried to get out of bed to take it from me, but was unable to do so. He was all a-tremble, and had no more strength than a two-year-old child.

When the bottle was about three-fourths empty he fell asleep and slept for about twelve hours. He was so quiet that for a time I thought he was dying, and was on the verge of calling in a doctor, contrary to his instructions However,I couldn't disobey him. I lay beside him on the bed, crying bitterly, and when he finally awoke the sound of his voice as he stroked my head was a never-to-be-forgotten joy. I cried now with happiness, and when he asked me for a cigarette I lit one and held it to his lips as his hand sought mine and stroked it affectionately. He asked for a drink of water and I held the glass to his lips, nearly choking him in my eagerness to get the water down his throat. He drank five or six glasses of water, smoked several cigarettes, and fell asleep again. With contentment in my heart, I undressed and got into bed.

He woke me several times during the night for water and cigarettes. When morning came he sent me to our landlady to ask that tshe make some soup for him. She was most sympathetic, telling me that she knew just what would be best for a man in his condition, and that she would provide for him. She kept her promise, and several days later Curly was up and around, although still too nervous to shave himself. He looked funny with a week's growth of hair on his face.

I returned the roll of bills which he had given into my care, and about ten days later we rambled out of Louisville and went to Indianapolis. We stayed there about ten days, and Curly received another lot of phoney jewelry which he peddled. I did not do nearly as well there as in Louisville; about three dollars a day was my average. As neither of us liked the city, we started for Toledo, Ohio, which he said was a good town. We planned to work only the larger cities, like Cleveland and Buffalo, until we reached New York.

He estimated that by that time we would have nearly a thousand dollars to tide us through the winter. He told me we already had close to four hundred dollars, and tnat he expected to sell quite a lot of stuff in Toledo. He punned the name of the city, singing "We're going to To-le-do, to lead a better life." I liked it.

We stopped off at Fort Wayne, Indiana, and that stopover proved to be our undoing. We had entirely given up seeking the company of other tramps in the jungles; in fact,I don't recall any meetings since we left new Orleans Frenchy and Cincinnati Red after our encounter with them. We went up town, where he played a joke on me by telling me about a "rose-water fountain" which he promised me I would enjoy. When we were half a block away, he bade me hold my nose until I had sampled its contents. He led me to a fountain in front of the Court House, to which several drinking cups were attached, and filling one with water, he bade me drink. I took one mouthful and dropped the cup; the water had a sickening taste and smelled like rotten eggs. I was angry for a moment, then joined in his laughter and playfully kicked him.

Before we had gone more than a block, we were in serious trouble. A man, accompanied by an officer, came up behind us and stopped us. The man told the officer that Curly had swindled him, and we were promptly arrested. I had no idea what it was all about until we got to the city jail. There the man claimed that Curly had sold him a phoney watch a couple of months before, representing it to be gold, and had told him that he was a railroad trainman out of work. They locked us up in separate cells after I had given the name Curly had told me to use in case of a "pinch", and told the officer that Curly was my father. Curly's accuser stated that he had recognized Curly as we stood before the fountain and had followed us, picking up the arresting officer on the way.

Curly was tried the next morning, convicted of petit larceny, sentenced to thirty days in jail, and led away. I was taken back to jail where, after a long grilling, I admitted that Curly was not my father. I gave my right name, but insisted that both my parents were dead. A few days later I was sentenced to the reform school at Plainfield, Indiana, until I became twenty-one, unless I was sooner paroled. In contemplation of ten long years to serve, I cried my heart out.

Jungling, 1895

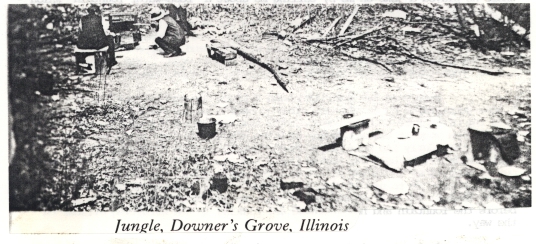

Jungle, Downer's Grove, Illinois

Pictures from "Knights of the Road -a Hobo History",

Roger A. Bruns, Methuen, 1980.