Chapter 7

Curly and I went uptown, engaged a room, and bathed. After lunch he asked me if I had ever visited the "Chicken Soup Springs" on the outskirts of town. I thought he was kidding, and replied that the feathers tickled my throat. He assured me that it was true, and though I didn't believe him I accompanied him to Bock's Hot Springs, where we drank several cupfuls of the so-called chicken soup. We seasoned it with salt and pepper. The water had a mild chicken-like flavor, and I am sure that if it had been served as chicken consomm‰ in a restaurant, well-seasoned and piping hot, no complaint would have been made.

When we returned to our room, Curly told me of his wanderings since the Fort Wayne affair. He had kept in the background because of his regard for my parents and my own welfare; but when he learned of my trouble in Denver he concluded that I would probably get into trouble again, and planned to meet me upon my release from Golden. He had been advised that I wouldn't be released until February, and when he learned from mother that I had gone to the Coast, he had followed and tried to find me.

I told him of my experiences in Golden and of my trip to Australia. We spoke of the future, but he would make no plans other than that he wanted me to go to Denver with him. He told me that he was still peddling phoney jewelry, but that the Westerners were pretty wise and that the take was none too good. He had found a new field for it, however, in the bawdy houses. He did not represent it as being gold, but merely as gold plate over a gold-colored base which would last for a year or two. However, as he received from seventy-five cents to two dollars for articles that cost him from ten to fifty cents, he managed to make out quite well. His swindling had now become merely unlicensed peddling. The stuff he sold was similar to, but of better quality than the stuff now found in five-and-ten-cent stores. He grinned when he told me that he did not always receive cash in payment. Barter and reciprocal trade agreements are nothing new!

Late that afternoon we went to the Express Office, where Curly received a large valise that he had shipped from Reno. When we opened it at the room he displayed a large and, to me, amazing assortment of jeweled rings, brooches, and bracelets. I asked him if he had burglarized Tiffany's, and he laughed. He said he bought most of it from an importing firm in New York, and that it was made in Belgium and Holland. I could hardly believe that so much magnificence could be bought for so little.

After supper we walked about the streets, and then went to a theatre showing Uncle Tom's Cabin. The next day, Curly loaded his pockets and mine with small boxes containing jewelry wrapped in tissue paper. It was afternoon when we started on a round of the hookshops (the girls usually slept till noon), and by six o'clock he had sold at least twenty-five dollars' worth. He was propositioned several times, but declined. He had instructed me to say little and study his methods. He lied outrageously about the cost to him of each article, and always set the price above what he expected to get. I learned that hookers enjoyed a bargain as much as other women. He was offered liquor, but refused it; I was glad, for I had not forgotten my experience with him in Louisville.

That night Curly asked me to give up mooching and try peddling, and I agreed. He proposed that I try private homes, and the next day I did so with fair success considering my inexperience. I sold about six or seven dollars' worth of jewelry that afternoon, and on the way home--it was a hot July day --I went into a saloon and ordered a large glass of lemonade. The saloon was also a gambling house with a wheel, a couple of faro layouts, and several stud poker tables. They were not busy at that time of day, and when I showed the bartender some of my samples he called some of the housemen (gamblers) up to the bar. I told them frankly that the stuff was phoney. It was a new gag to them, but almost to the man they bought, without quibbling over the price. Half an hour later I went to my room with about twenty dollars more in my pocket, and orders for several articles of which I was short. One, I recall, was a gorgeous matted chain bracelet encircled with three rows of red, green and white stones, for which I had received five dollars. Considering that somebody once sold a string of beads for Manhattan Island, I was still a piker. However, as I wasnt selling to a bunch of Indians but to a lot of so-called wise guys, I didn't feel badly about it.

Curly was surprised at my success. This new outlet that I had opened up had not occurred to him, and his praise was unstinted. He insisted that I retain all of the profit from my sales and carefully figured out the cost of what I had sold, which was all he would take from me. He made it clear that he no longer considered himself my jocker, but that I was his pal and partner. He advised me to lie to other tramps about my age, if asked, and to tell them I was nineteen. Younger tramps were looked upon as runaways from their jockers, and were regarded as renegades.

Curly completed his round of the hookshops, and the next day we completed our calls on the saloons and gambling houses. We had fared quite well in Ogden, and moved on to Salt Lake City as paying passengers. It was the first time since leaving Springfield that I had ridden on the cushions.

Business at the "Lake" was very good. There were hookshops and gambling houses galore. It reminded me of Denver bacause of the running water in the streets and the centralized red-light district. As in Ogden, I sold mostly to gamblers and bartenders, and we were all of two weeks peddling the City. We had a nice room in a second-class hotel, and each evening after supper we either went to a show or stood around the gambling tables watching people play Faro and Roulettte. On one of these nights I saw a drunken miner whip out a gun and take a couple of shots at a Faro dealer whom he claimed was cheating. The miner was a bum shot, for although he was no more than six feet from the dealer he missed him completely. A bouncer took the miner's gun away from him and threw him out. The dealer continued his work as though this was an everyday occurrence.

When we were ready to leave the Lake, Curly sent most of his stuff to Denver by express. We went to two tramp hangouts and left a ten-dollar gold piece at each one with the tramps we found there. Curly told me that by doing so, he enhanced our reputation and that, as he was but little known to Western tramps, he wanted to gain their good will and become known as a square shooter.

The night we left the Lake we rode a blind to Provo, where we were ditched. We found an empty box car on a freight on a siding, and when the freight followed the passenger train out of the yards we spread out some newspapers, lay down and went to sleep. No shack disturbed us, and early in the morning we reached the town of Price. After a washup and breakfast, we looked the place over. It was a division point, I think, but quite small. We found only one hookshop, which had a switchman's red signal flag nailed to the door and a red-chimneyed lantern hanging above it. There were two or three saloons, and our take in the town was less than two dollars. We met several tramps there; Curly knew two of them, and we cooked and ate a big mulligan. For the first time, I saw my monicker coupled with Curly's when he carved on a water tank

MICH

CURLY B.E.

CHI

CURLY

Our next stop was in Grand Junction, Colorado. It was also a division point, but larger than Price. We peddled the town the day we arrived. That evening we jumped the blind baggage of a passenger train and rode to Glenwood Springs, where we were ditched during the night. The town lay in the mountains, and the nights were quite cool. We went to the depot and stayed in the waiting room, which was partially warmed by a small stove in the station agent's office. We slept fitfully the remainder of the night on the wooden benches. When we awoke we washed up and shaved in the station's small lavatory, which the agent had evidently forgotten to lock up, as was the usual custom in small towns.

We had breakfast at a Chinese restaurant, and when we paid the Chink, he told us of the fine swimming to be had in the river which flowed past the railroad station. We had not noticed the river because we had left the station by the back entrance, but as we walked toward the station we noticed what appeared to be a wispy light fog rising in front of it. We passed a small general store, in whose window was a poorly lettered cardboard sign reading, "Bathing Suits for Sale, or Rent". The last two words apparently were an afterthought, for they were printed on a piece of white paper which was pasted to the cardboard beneath the other words. When we reached the river, we found a small stream not more than a hundred feet across; it seemed to be shallow, as several small boulders jutted above the surface. We were surprised, on putting our hands in the water, to find it quite warm, and the mist we had noticed proved to be vapor rising from several hot springs that bubbled to the surface near the bank. I suggested renting bathing suits, but Curly thought we might find a place where they would not be needed. We walked down stream over rocks and boulders for a short distance, and came upon a small pool in which two young women were swimming and splashing each other. We stopped to watch them, and presently they climbed out of the pool and stood on a large rock not more than fifty feet away, turning their bodies as they dried themselves in the sun. They were probably the wives or daughters of some of the natives, for we found afterwards that there were no hookshops in the town. We remained hidden until they had dressed and gone.

The Jew who owned the general store rented us skirted bathing suits for fifty cents each. We changed clothes in a back room of the store and went down to the river again, where we lolled about in the shallow water near the stastion until mid-afternoon. It was delightful there with mountains all about us, some of the distant peaks still showing patches of snow, and I was reluctant to leave; but that night found us on top of a freight train (all the cars were sealed) bound for Leadville. We lay on our bellies, as it was tunnel country, on top of the second or third car from the engine in order to get as much warmth as we could from the engine's smoke, for the night was quite cold. Our nearness to the engine nearly proved our undoing, for in the first tunnel we passed through the red-hot cinders beat down upon us like fiery hail from Hell, getting down our necks and burning blisters on our backs and hands. When we turned about, the cinders went up our pants legs. Fortunately, the tunnel was a short one. We crawled back some six or seven cars where the air was free from the smoke that had blinded and choked us; and now it was cold. Riding the deck of a boxcar on a narrow-gauge railroad, with the train rounding sharp curves, is no picnic under the best of conditions. One expects the train to topple over at any moment, and instinctively sidles over to the outside of a curve to help balance the car. We were glad to climb down at the next stop, a water tank and telegraph station, where we built a small fire of brushwood and slept on the bare ground beside it for the rest of the night.

We couldn't buy, beg or steal any breakfast there. Curly carved our monickers on the tank. We washed up as best we could and went to the telegraph station, where we learnet that there wouldn't be any eastbound train until about midnight, when the only daily passenger train came through. The operator said this train had to stop for orders and water but that it was a hard train to beat, We decided to board it and pay our way to Leadville, an untrampish action to say the least, and one which few tramps could afford. We were so famished we had the train "Butcher" jumping up half the night bringing us bananas, candy and peanuts. At Leadville we had a grand cleanup, buying new shirts and Stetson hats, after which we filled our bellies, rented a room, and slept until the following morning.

Leadville was a large town, with more "dens of iniquity" than one could shake a stick at. We stayed there about four days and sold all the small stock we carried except for a few wide, oval-topped wedding rings which proved to be poor sellers. I had several in my vest pocket and was wondering where I could sell them. I had stopped before a jewelry store, in front of which stood a young woman looking at some trays of rings displayed in the window. I made some remark about the nice-looking rings, more than half expecting a rebuff. She did not get uppish, and I was wishing I had some of our classy stuff to show her. We talked for a minute or so, and finally I fished one of the wedding rings out of my pocket, told her it was phony, and said something about how much fun she could have making her friends believe she was married. She became interested at once, and bught two rings at $1.50 each; one, she said, was for a friend. From that day on, wedding rings became one of our best sellers in the cities and nearby small towns. I sold many hundreds of them during the next two years to factory workers (both men and women), store clerks, school teachers and others, my spiel to the men being something about how nice it would be, when registering at a hotel with their best girls, to have the hotel clerk glimse that badge of respectability upon their sweethearts' fingers. Women, I learned, were no more virtuous then than now, although quite a bit more careful.

I had found a new outlet for our stuff which was to serve us in good stead a few months later when, due to high tariffs or failure of either the importer or manufacturer, we were unable to get supplies of the more flashy jeweled stuff. We could still get American-made jeweled rings and brooches, but they were an inferior product and what was worse, they showed it. The wedding rings cost eighty-five cents a dozen for the cheaply plated ones; the "acid-test" ones cost about $1.25 a dozen in gross lots. We used the acid-test ones, carrying a small bottle of nitric acid and a testing stone with us, and representing our wares as being "gold rolled". We carried a few of the cheaper ones to demonstrate with. We had learned that one rub of the upper face of the cheap ones on the testing stone would make a mark that turned bright green when a drop of acid was placed on it. We could give the edge (not the face) of an acid-test ring several light rubs without cutting through the gold. It would fool some jewelers, but not a pawnbroker.

After leaving Leadville, we made the rest of the trip leisurely.

We rode through the Royal Gorge in an empty boxcar with both side doors open and, as we were going downhill, we traveled pretty fast.. At one moment we thought we were going to be thrown into the Arkansas River a thousand feet or more below, and the next, we expected to be dashed against the canyon wall. I truly believe that at some points the canyon wall was less than a foot from the side of the car. That trip was the first time that either of us had ridden on a narrow-gauge railroad, for we had gone to the coast via the Union Pacific. Later on I got used to it. We rested a day at Salida, and stopped over for a day or two at Pueblo. We visited the notorious "Bucket of Blood" saloon, gambling house, and variety show, and climbed the mesa south of the river. We continued on to Colorado Springs, and walked over to Colorado City and through the Garden of the Gods. We made a feeble attempt to climb Pike's Peak, but gave it up after a mile or two when our legs and breath gave out. We reached Denver the next morning, and I was delighted to feel my mother's arms about me and to hear her comforting voice again.

We took mother to Tortoni's, a high-class restaurant, and after supper went to the Tabor Opera House for the show. Maybe it was one of the Kiralfy Brothers' extravaganzas, or maybe Nat Goodwin, Otis Skinner, Julia Marlowe, or Modjuska. It was a good show, and definitely did not have Lillian Russell in the cast; mother could never view the wearing of tights with equanimity.

The next night, mother, Curly, and I held a conference regarding my future. Mother wanted me to go to school or learn a trade. I wanted to continue on the road with Curly. Curly was between the devil and the deep blue sea. He wanted me with him, yet he supported my mother's contention. He said that the phoney jewelry racket was about played out in the East and South, that the West would be the same within a year or two, and that tramping as a career would only make me a drunken sot.

That night Curly told me how he became a tramp. His father and mother, still living, were well-to-do and had seen him through high school, after which he had gone in with his father to learn the fur business. He had not liked buying and selling raw pelts and gave it up to enter a wholesale provision house. He graduated from the shipping department to outside sales, and married the daughter of a rich lumberman when he was twenty-five. After two years, he and his wife quarreled and separated. He took to drinking heavily, and though he managed to secure good positions from time to time, his periodical sprees were not tolerated by his employers. Finally, he found it impossible to obtain work because of lack of references. He left Detroit, went to Chicago, and worked as a bookkeeper for a lumber firm until his next spree. After being discharged, he started tramping about the country, first begging and then selling phoney jewelry. He had been tramping for six years, he said, going home for a couple of months each winter to be with his parents and to see his son and daughter, at which times he managed to refrain from drinking. He told me that for more than a year now he had conquered the desire to get drunk, that he was satisfied that he had mastered the habit, and that when he went home this coming winter he intended to seek a reconciliation with his wife who, he said, still loved him, and see if he couldn't rehabilitate himself.

Tears came to his eyes when he spoke of his children, and my hand sought his in a comforting gesture. I was pleased to learn of his apparent victory over the liquor habit and promised that, if he would take me east with him, I would return to mother and go to school, during the winter at least. I reminded him of his promise to take me to New York, when we first met under the water tank in a small Indiana village, and he laughed. I promised mother that I would take good care of myself and not get into any more reform schools, and for the first time in my life I asked for her consent. After questioning Curly, in whom it was clear she had considerable confidence, she agreed, and I was jubilant. I hugged both of them and I could see that Curly, too, was pleased.

Curly and I stayed in Denver for almost a week before leaving. I did not dare do any peddling in Denver because I was under parole from Golden and had to write a letter to the superintendent each month giving an account of my activities. I had been required to do the same for the Plainfield school, but had discontinued doing so when we first came to Denver. However, I had decided to give Indiana a wide berth on our way east.

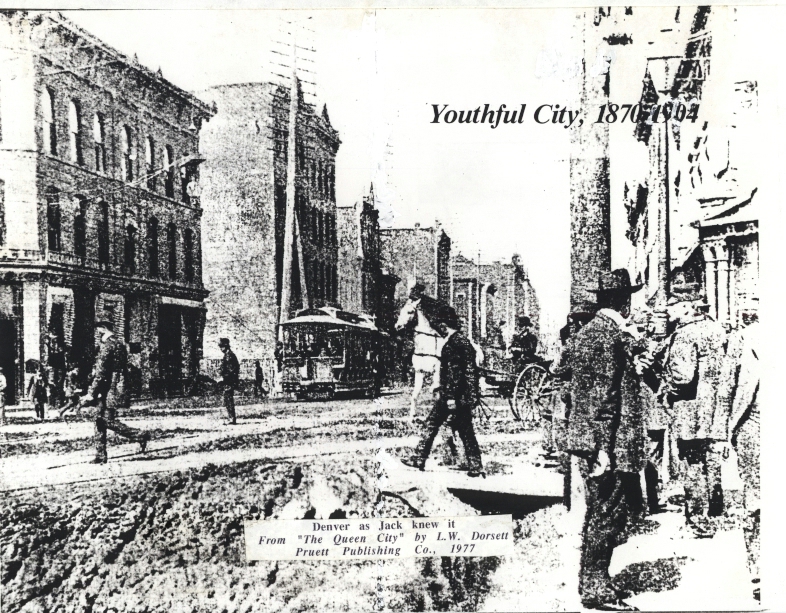

While Curly was working, I bummed around town. I used to stand by the hour at the southeast corner of Seventeenth and Holliday streets (Market Street then, I believe) watching Soapy Smith sell suckers what appeared to be twenty-dollar bills wrapped around a small piece of soap, for a dollar each. Although he told his customers not to open the package in the crowd that stood about, every once in a while a "purchaser" would do so, bringing to light a perfectly good twenty-dollar bill. He was a copper or shill, of course, and would gleefully wave the bill around his head as he elbowed his way out of the crowd--to return half an hour later and repeat the performance.

Soapy was clever, and worked entirely within the law. He had a police permit, I had been told, to peddle soap on the city streets. He stood upon a small raised platform which he kept stored in a nearby saloon when not working. He usually worked from about noon until five P.M., when he would close his valise, fold up the canvas-topped collapsible stand on which the valise was setting, and depart.

When he opened up for business he would get a crowd about him by having one of his helpers play a mouth organ. He would then launch into s short spiel about the wonderful properties of the marvelous Yaqui Indian Cactus Soap. He would remove the wrapping from a piece of it, no larger than half of a man's little finger, and after showing the crowd a twenty-dollar bill he would wrap the bill around the piece of soap, replace the original wraping, and press the small package against the sharp metallic edge of the valise, cutting the outer wrapper in such a way as to leave a portion of the bill exposed. He would then wave the package before the eyes of his audience and toss it into one side of the flat-sided valise among some hundred or more unbroken packages, stir them up with his fingers, and offer to let anyone pick the money-wrapped packet out of the lot upon payment of one dollar, meanwhile emphasizing that he was selling the soap and not the twenty-dollar bill.

The purchaser was permitted to paw over the lot, until he found the packet which he fondly hoped would be the lucky one, and which he identified by the exposed green underwrapping. There would be several in the crowd offering dollars to Soapy, but the first purchaser was always a capper; and while the capper was searching through the numerous packages, Soapy would be wrapping other twenty-dollar bills around other pieces of soap, one of which he would apparently toss into the valise as soon as the first piece had been withdrawn, thus keeping the ball rolling as long as an upraised fist with a dollar in it was in sight.

When the crowd stopped buying, Soapy would fold up the valise, make some biting remark about the timidity of tenderfeet, and go into the saloon. When the crowd had dispersed, he would come out and start the ballyhoo all over again. He was so clever that, although I knew his pitch was a swindle, I often found myself with my hand in my pants pocket, scratching my fingernail over the milling of a silver dollar, and with an itch in my credulous mind to buy at least once. The suckers, of course, found only a piece of green paper about the size of the revenue stamps customarily pasted over the bungs of beer barrels.

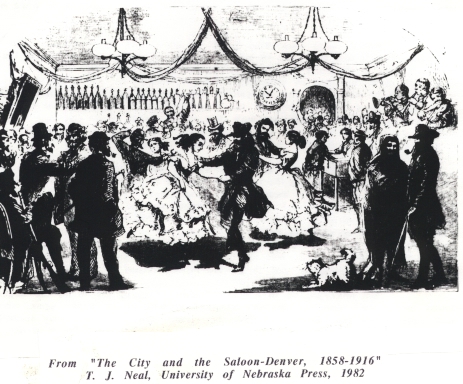

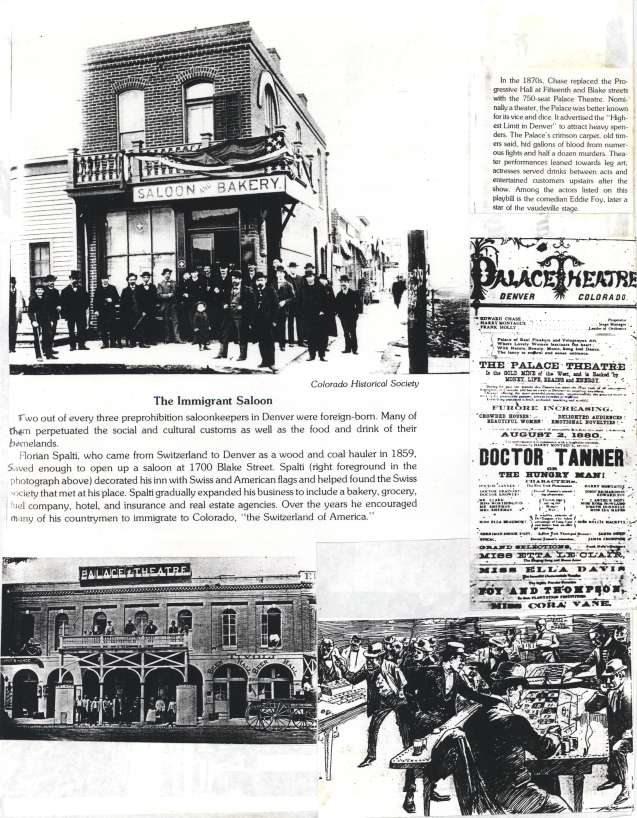

Denver, in those days, was a stinkpot in more ways than one. Holliday Street (ex Market) from Seventeenth Street to Twenty-second Street was packed solidly with hookshops on both sides of the street, with the Central and Haymarket theatres --both low variety houses--wedged in between. Saloons in the downtown district were everywhere, while gambling houses lined the north side of Lorrimer Street from Sixteenth to Nineteenth Street. To add to these moral stinks, there were the sulfurous fumes from the Argo Smelter north of town which, when the wind was from the northeast (as it frequently was), made it impossible to get a breath of fresh air. The streets, however, were kept clean; water ran down the gutters of most of them, as it did in Salt Lake City. To lie in the gutter there was to lie in Denver"s cleanest spot; yet I lived in Denver long enough to see the entire city, beginning shortly before Mayor Spee's administration and while he was head of the Board of Public Works, become one of the most desirable spots on earth.