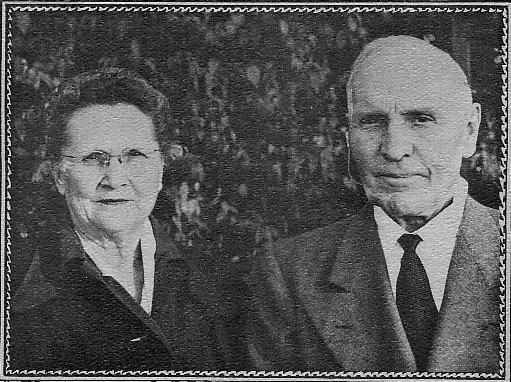

THE STORY OF LESTER BURT FARNSWORTH AND HIS WIFE, ROSINE NIELSEN FARNSWORTH