Computing Form Factors

By Wayne Maruna

The change in the power of personal computers has been well documented. But I find the change in computer form factors to be just as significant to their modern day usage. The Computerworld website provides a simple definition of the term: “Form factor refers to the overall dimensions and component layout of a device—in other words, its physical size and packaging.”

When personal computers were first introduced into the non-hobbyist consumer market, they were truly desktop computers. They literally sat on your desktop, occupying real estate about the size of a large place mat. The CRT monitor sat atop the desktop computer. Before long, the machines moved from the desktop to the floor by standing the computer on its edge, creating the ‘tower’ computer. Today when we speak of desktop computers, we almost always are referring to tower type machines. More recent modifications to this style include the so-called Slim-line towers which are perhaps half the width of a typical tower unit, achieved primarily by changing the axis of the optical drive (CD or DVD) from horizontal to vertical while shoe-horning in all internal components. Some manufacturers have abandoned the separate case altogether, melding the electronics and drives into the monitor assembly to create a so-called All-In-One desktop PC.

Shown: Desktop, Tower, Slim Line, All-in-One

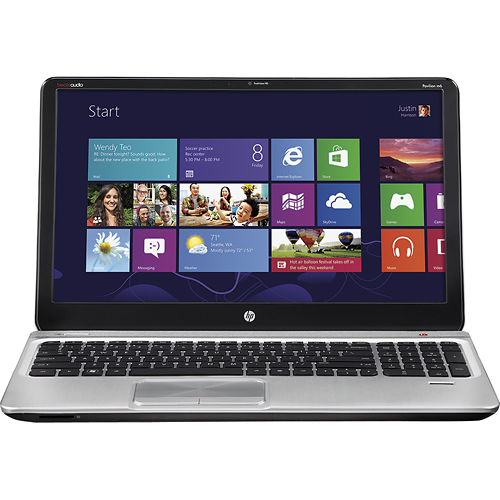

The first portable computers were more aptly called transportable and were the size of accordions. These came out about the time O.J. Simpson was shown on TV running to the Hertz counter, apparently to rent a Ford Bronco. Trust me, you did not run when lugging one of these old ‘transportables’. Then the form factor mercifully changed to the laptop style much like we have today. Screens were in the 13” to 14” range, restricted as much as anything by the cost of producing such thin monitor screens. As technology improved and costs decreased, laptop screens got bigger, eventually topping out at around 17” at which point they were considered ‘desktop replacements,’ meant more for a kitchen desk area than transporting on business trips. In May of 2012, HP reported that the 15” screen models were its most popular laptops in the U.S.

Next out of the box were the so-called Netbooks which had their heyday about five years ago. These were laptops that looked like they had been left in the dryer too long. Screen sizes shrunk to typically around ten inches and keyboards were proportionately reduced in size. They had the advantage of being light weight and therefore easy to carry, plus thanks to their power thrifty Intel Atom processor chips, could go as much as eight hours on a battery charge.

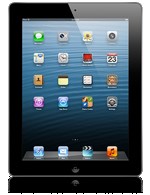

But then came the Apple iPad, and suddenly tablet computing was all the rage and remains so today. Tablets marked the death knell of the Netbooks. While it was not the first so-called tablet computer, the iPad certainly set the market for the form factor. By jettisoning a physical keyboard in favor of a virtual keyboard, and by eliminating any optical drives, the tablet computer could be as thin as a dinner plate and about as heavy. My iPad, with limited use, can run for days on a charge. Tablet screens generally range from 7” to 10” in size, measured diagonally.

I don’t include dedicated E-Readers (like the Kindle and the Nook) in my own definition of tablet computers, but they are certainly related. Upgraded products like the Kindle Fire and Nook Color blur the line between tablets and E-Readers, as there are elements of both contained within. Inasmuch as they can handle email and web browsing, the Fire and Nook Color do fall within the scope of a tablet, though with some limited functionality.

Shown: Nook family of reader and tablets, Kindle Paperwhite, Kindle Fire HD

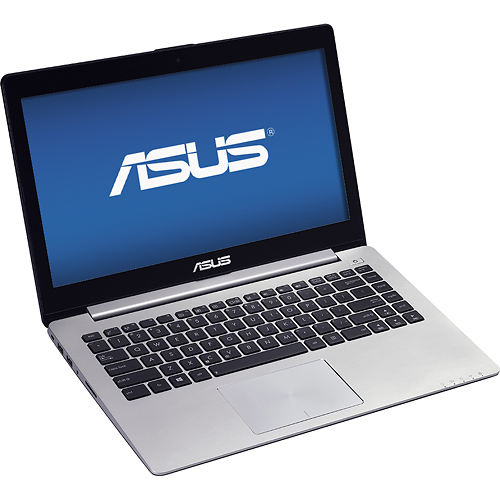

Not everyone can deal with the lack of a

physical keyboard on a tablet. Most manufacturers do provide for wireless

(typically Bluetooth) connectivity to an external keyboard, but then you are

carrying two devices. So the hot buzzword at the 2013 Consumer

Electronics Show in Las Vegas was the so-called Ultrabook, which is actually a

trademarked Intel marketing term applied to thin laptops that meet certain size

and component requirements. The Apple MacBook Air is a leading member

of this genre. Light, battery efficient, and incredibly thin with a typical 13”

screen, these devices are ultra portable. Like tablets, they forego optical

drives while still incorporating keyboards. But their prices are neither thin nor light

weight. Expect to pay upwards of $1,200 at this time for an Ultrabook device.

you are

carrying two devices. So the hot buzzword at the 2013 Consumer

Electronics Show in Las Vegas was the so-called Ultrabook, which is actually a

trademarked Intel marketing term applied to thin laptops that meet certain size

and component requirements. The Apple MacBook Air is a leading member

of this genre. Light, battery efficient, and incredibly thin with a typical 13”

screen, these devices are ultra portable. Like tablets, they forego optical

drives while still incorporating keyboards. But their prices are neither thin nor light

weight. Expect to pay upwards of $1,200 at this time for an Ultrabook device.

Many of us carry so-called smart phones. Are these computers? Well, in a sense yes, though not in the traditional way of looking at computers. But I recently acquired a Samsung Galaxy Note II smart phone. It has a 5.5” screen, huge by today’s smart phone standards. (The newest iPhone 5 has a 4” diagonal screen, up from 3.5” on its predecessors.) As much as I love it, I must admit it would be an advantage to have an orangutan thumb to reach the far side of the screen when clicking on icons or on the keyboard. The Note II also comes with a stylus that allows you to write and draw on the screen and save to a file. Is it a phone? Absolutely! Is it a tablet? Well, sort of. Actually, a new term has come into being to describe such a device: a phablet. I do hope someone comes up with a better term soon because that one just does not roll off my tongue.

A person is certainly left to wonder where we go from here – and you can be sure that the manufacturers are doing the same. It’s a couple of years old now, but if you haven’t seen it, check out this remarkable video from Corning Glass showing their vision of an electronics-embedded future: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LE50vaI1ZeI

I still like the idea of having computer-free workstations set up with all the peripherals – monitor, keyboard, printer, mouse, but no computer. You would wear the computer on your belt or carry it in your purse - a smart phone descendant perhaps. You plop yourself at the workstation, your small device automatically connects wirelessly with all your peripherals, and you’re off and running. That would work for me.

Just don’t talk to me about computer implants – at least not until you’re ready to explain to me, in great deal, how the reboot process would work.