The Tablet Phenomenon

By Wayne Maruna

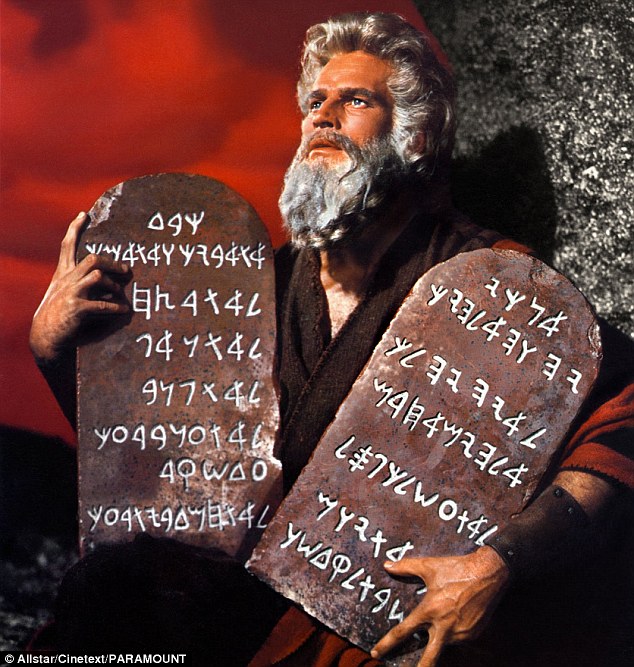

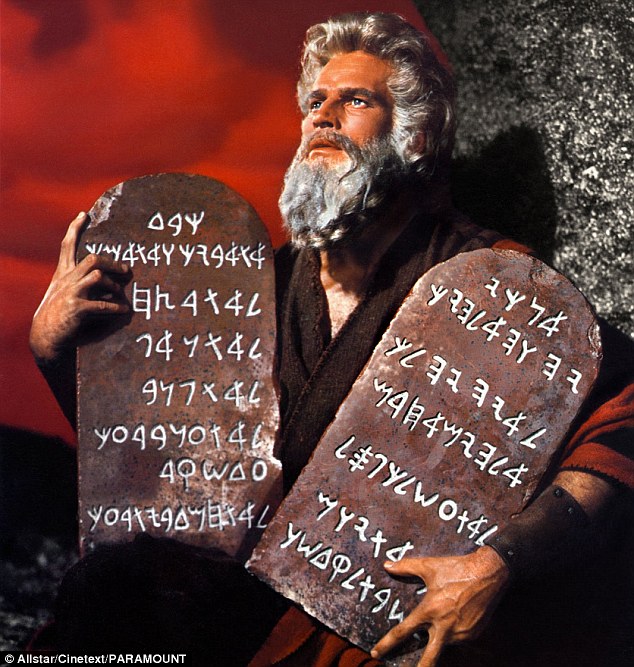

Tablets may seem like fairly new devices, but remember Moses brought

the Ten Commandments down from the mountain on a pair of tablets. With

respect to modern electronic tablets though, we tend to think that

Apple started the whole thing with their iPad. Actually there

were a series of devices, including PDAs (Personal Digital Assistants),

dating back before 2000 that were forerunners of the modern smartphone

and tablet. Perhaps the first device that was actually called a Tablet

PC came from Microsoft around 2000 and was generally considered a

failure. I don’t think there is much debate that the popularity

of the tablet as we know it today started with the launch of the Apple

iPad in 2010, and it remains the top rated tablet today by most

accounts.

But Apple is far from the only tablet producer in today’s market, which

is primarily segmented by the operating system employed: the

Apple iOS (shared with the iPhone), Google’s Android, Microsoft

Windows, and Amazon Fire OS, which is a heavily modified version of

Android. When one buys a tablet, they are not only buying into the

hardware, but also the whole of what is referred to as the tablet’s

‘ecosystem’, which includes the operating system, the available app

store, and the manufacturer’s update policies.

Microsoft markets its Surface tablets primarily to business,

professional, and commercial clients who have need of the full

Microsoft Office suite. Their earliest surface tablets ran a

version of Windows called RT which was poorly received in the

marketplace. Newer models run Windows 10 and can use Windows

application software. Surface tablets tend to run toward the high

end of the price scale.

Apple followed up its

hit iPad with the smaller iPad Mini and the recently introduced large

format iPad Pro. All three run Apple’s iOS operating system. All

software applications must be obtained from the Apple Store, which

boasts the largest collection of tablet program applications (or

‘apps’.) Apple’s prices for the various models at the time of

this writing start at $269 for the older model iPad Mini 2 with 16GB of

storage, and climb all the way to $949 for the iPad Pro with 128GB of

storage.

Google licenses its Android

operating system to a number of partner hardware producers, including

Samsung, Lenovo, Dell, Asus, HTC, LG, Sony, and pretty much anyone else

not named Apple. Each of these manufacturers is allowed to modify the

system to add their own unique apps or user interface. Google

also partners with certain manufacturers, like Asus and HTC, to produce

tablets marketed under Google’s own Nexus brand name. These are

said to run ‘pure Android’ as Google intended. Google often

updates its operating system, and the Nexus tablets are the first to

receive the updates. All others may or may not follow, as there

is added complexity to adjust the updates to accommodate the vendor’s

own unique modifications. Similar to Apple’s Store, Google maintains

the Google Play Store, which is the main repository of available apps

for Android tablets and phones.

Amazon’s Fire

OS is based on Android but has been heavily modified to tie the user

into Amazon’s own app store and exclude users from the Google Play

Store. More so than the other tablet makers, Amazon markets the

various Fire models to consumers who favor reading and entertainment

(movies and music) apps. People who have purchased Amazon Prime

memberships for $99 annually gain certain benefits from using Fire

models. Amazon has recently replaced some of its higher-end

models with lower spec models in order to sell them at more consumer

friendly prices. Their latest Fire 10 model with a 10.1” screen

and 16GB of on-board storage was on sale recently for as low as

$179. To hit this price point, the screen resolution, measured in

pixels per inch (ppi), was compromised to measure 149 ppi, one of the

lowest numbers on current tablets. By comparison, their prior

year model, the highly regarded $400 Fire HDX 8.9, had a pixel density

of 339, higher than even the 264 ppi of the iPad Air and Pro. (Pixels

are essentially a pinpoint of light, and the more you can pack into a

given space, the sharper the displayed image.)

There are many factors that go into the selection of a tablet.

Perhaps the most obvious is screen size, which generally ranges from 6”

to 10” measured diagonally. Most are found in a range of 8” to

10” sizes. The iPad Air measures 9.7”, the Mini comes in at 7.9”, and

the new Pro model is 12.9”. The new Amazon Fire 10 has a 10.1”

screen, while the latest Google Nexus 9 is 8.9”. In addition to

size, price is driven by on-board storage, which ranges from 8GB on the

low end to 32GB on most tablets, 64GB on some tablets, and 128GB on a

few. Note that on an 8GB tablet, after you deduct for the

operating system and a few other things, you only have about 5GB

available for personal storage; on a 16GB model, that available number

is just over 11GB. I recommend 16GB as a minimum, with 32GB

preferred. Most tablets manufacturers allow you to store your

music and movie media in their respective ‘cloud’ so more space is not

necessarily worth the up-charge.

With

increased screen real estate comes increased weight, though newer

models tend to be thinner and therefore lighter. Weights

generally range from around 10.5 ounces for 7” to 8” tablets to about

15.5 ounces for 10” range tablets. A few ounces may not sound

like much, but if you’re holding a tablet for any length of time, you

can tell the difference, which is why most people purchase matching

combination case/stand units.

Tablets have

become common in households because they are just so handy. In the next

two monthly issues, I plan to talk about a hands-on comparison of four

tablets that use three of the tablet ‘ecosystems’.