Amigo

Supercharge/Turbo Charge Page

Because it got

so big, it needed it's own page.

Supercharge vs. Turbo Charge. What's the

difference?

- Supercharger: A

supercharger is mounted on a bracket in line with the crank belt. As the

crank rpm increases, so does the impeller rpm in the supercharger. Air

is drawn into the supercharger and compressed by the impeller and fed to

throttle body. A supercharger typically operates at 40,000 rpm to

produce 6 lbs of boost.

- Turbocharger:

A turbocharger works on a similar principal as a supercharger system

except it is driven by the exhaust gases expelled from the engine. The

turbocharger is mounted onto the exhaust manifold. The exhaust gas

enters one side of the turbo. When the engine is hits a specific rpm,

the turbo 'spools up': the incoming gases force an impeller to rotate

inside the turbo. Fresh air is drawn into the other side of the turbo

from the intake and compressed by the rotating impeller and fed to the

throttle body. The turbo unit requires an oil feed to keep it cool and

lubricate its bearings. The turbo typically operates at 150,000 rpm to

produce 13 lbs of boost.

- Which is better:

They each have pros and cons. Which is best depends on your

application.

Con-Turbo: Heat problem.

Boost discharge from the turbo is subject to secondary heating from the

hot turbo casing and expands. This counteracts the purpose of the turbo

which is to compress the air. An intercooler (air-air cooler) and

pipework between the turbo and the throttle body becomes vital to cool

and condense the boost, increasing cost and complexity of fitting the

unit. The unit itself also undergoes a lot of

expansion/contraction stress as the engine heats it up/cools off.

Superchargers are mounted away from the exhaust and driven by belt--much

cooler, and although intercoolers are nice, they are not as required.

Con-Supercharger: The

supercharger is always spinning and moving air, even though it's not

always producing boost in the engine. (The supercharger produces boost

under high load conditions which may include heavy acceleration, going

uphill, passing another vehicle or under towing conditions.)

Superchargers offer the power you need on demand, the reminder of the

time the engine is working just like a normally aspirated engine, but

with the additional mechanical drag. Turbos run of exhaust gas,

and don't pull the engine down. Expect to lose about 2 MPG (more,

if it's a large supercharger) in regular driving.

Con-Turbo: Smooth performance. You

know in those old films where they hit "turbo" and get their

heads thrown back? If it was that good, we'd all use it and to

heck with mileage, but in reality there are some things to watch out

for. The major disadvantage of turbo is the wait for turbo to

come into boost. The turbo does not spool up (and the power boost isn't

available) until the engine hits about

3,000 rpm, and the wait is called the "lag time." When turbo does kick in, you feel

the surge of power. The turbocharger

delivers a majority of peak power almost immediately as it spools up,

putting a surge of power (and stress) through the drivetrain and engine

that could cause some long term problems on weaker-built, pure stock

vehicles. The fun part, however, is that power surge can cause the

driving wheels to lose traction driving in the rain, a really cool

effect if you plan on it. "Hey, baby, hold my drink and watch

this!"

- How much power could I expect

to gain ? Roughly, you can expect to gain about the same

power difference percentage as you gain induction pressure percentage.

The equation is HPafter = ((14.7 + boost)/14.7)*HP before. For instance,

if you have a 200HP engine and you add 7.5psi boost, you can expect to

have about 300HP. This is an estimate, not an exact calculation so take

it for what it is worth. For Superchargers, this calculation is about

80-90% accurate. For Turbo, I'd guess you should multiply that

equation by 50%. These losses are due to inefficiencies and air

density losses due to heating. (Even with Supercharger, intercooling

helps.)

- What is the difference between

a centrifugal supercharger and a roots type supercharger? A

roots-type supercharger is a positive displacement supercharger that

forces air into an engine with two rotating, intermeshing rotors. A

centrifugal supercharger has an impeller that pulls air through the

center and directs the air into a scroll using centrifugal force. The

scroll resembles a large blow-dryer with a circular shape and a

discharge tube. The air is directed in the scroll, pressurized and

forced out of the discharge tube and into the engine.

I decided to Supercharge. What are my options?

The best, non-biased info I saw on this was Supercharger

types by Dan Houlton http://frontpage.inficad.com/~houlster/Amigo/Supercharger/thoughts.htm

It's summarized below.

I've spent a lot of time researching super chargers and I've found what I

believe to be the best charger for what I want to do. Please keep in mind that

these are my opinions based on what I've read. I have no first had experience

(yet), but feel that the majority of my sources are reliable. You're free to

disagree with me so please don't send me any nasty letters about how

such-and-such supercharger is so much better than the one I chose.

- Centrifugal: When I first started looking, a centrifugal type

charger looked like the obvious choice to me since there are so many

aftermarket makers of these types for street vehicles. I now believe that

these are so popular not because of their overall performance, but because

they are the most efficient and impact mileage (and therefore emissions

maybe?) the least.

Basically, they work the same as the compressor side of a turbo

charger, but are driven by a belt off the crankshaft rather than a turbine

sitting in the exhaust flow. They spin in the area of 50,000 rpm or more and

are very capable of producing a lot of boost with lower overall horsepower

needed to drive them.

Need more boost? Just over-drive the blower a little bit and it

makes a big difference in what comes out. Because of the way they are

designed, spinning them twice as fast yields around 4 times as much boost.

But, this ability comes at a price.

Thinking of it in reverse, say you have a centrifugal set up to

give you full boost of 8 psi at 6000 rpm. This is great at 6000 rpm, but

down at 3000 when you're trying to get things moving, you're only getting 2

psi of boost. And at 1500 - 2000 rpm, there's almost nothing. Cut the

compressor speed in half, and you reduce the boost by 4.

So hey, lets just set up for max boost at 3000 rpm right? Well,

that doesn't work either. Assuming it doesn't blow itself or the engine up,

it'll be pushing 32 psi by the time it reaches 6000 rpm so you need things

like waste gates or dump valves to re-circulate the air to keep from over

boosting.

Overall, these types sold by companies like Paxton, Vortech and

ATI are very good within a narrow rpm range and work well in oval or

cross-country racing, but for street use and rock crawling, they just aren't

nearly as good performance wise as a Lysholm type.

- Roots: The Roots type blower is one of the oldest and most

widely used super chargers. Its biggest advantage is that it's a positive

displacement blower although it also has a lower efficiency than other

types.

It's used a lot in drag racing and is really big in European

road racing where the racers are continually on and off the throttle and all

through the rpm range. It's biggest advantage is that being positive

displacement, it produces substantially more boost at low rpm than a

centrifugal with the same peak boost would.

This is more like what I want for daily driving and off-road

use, but most of these are still for larger (and usually race) engines. They

are also inefficient and make a lot noise.

- Eaton: Another type is made by Eaton. It is basically a Roots

type, but this is a "twisted lobe". Although not a new idea, this

is supposed to make it a little more efficient and quiet than a strait lobe

Roots type. The fact that it has been used successfully in a number of

production cars in the last few years lends it a lot of credibility and also

has resulted in units sized for smaller engines such as a 2.6l. This is the

design I was planning on using until I started reading about the Lysholm

type charger.

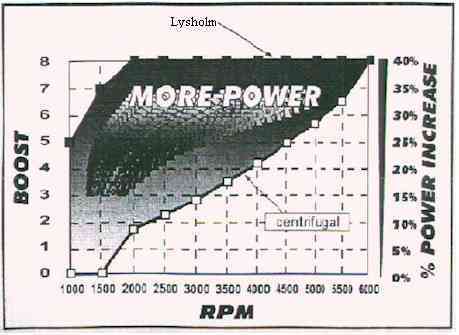

- Lysholm While the Eaton and the centrifugal are fine and do what I

basically wanted to get more power for passing and long hills on the

highway, I found that there is another type that will give me not only that

same top-end horsepower, but extra low and mid-range torque as well.

This is the Lysholm or "screw type" of supercharger.

It's different than the others in that it truly compresses the air rather

than just blowing really hard to make it pile up in the intake manifold and

produce boost. This means that boost is not dependent on rpm. You can make

full boost at as little as 1800 - 2000 rpm and keep it there all the way up

to red-line.

What this means is that you get much more boost where you need

it most. Right in the low and mid-range where your engine spends most of its

time (unless you're a road racer). With the Lysholm you have much more power

down low where it does more good. More importantly for me, this means I can

get the benefits of boost at low-rpm where most of my off-road time will be

spent.

This is best seen with the graph shown below.