“Uncle Marvin was a beautiful young man with greenish blue eyes and blond hair, a man of laughter and fun” as my aunt Marjorie says, you know she told me just how much in love they were, when she was fourteen and he was fifteen years old, how he’d joke and fun around with her, how she’d help wash dishes at grandma Pierson’s house and Marvin would dry the dishes and let granny rest.

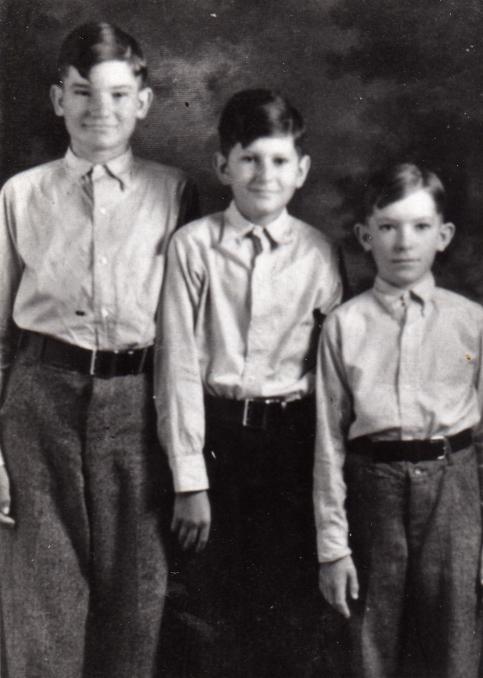

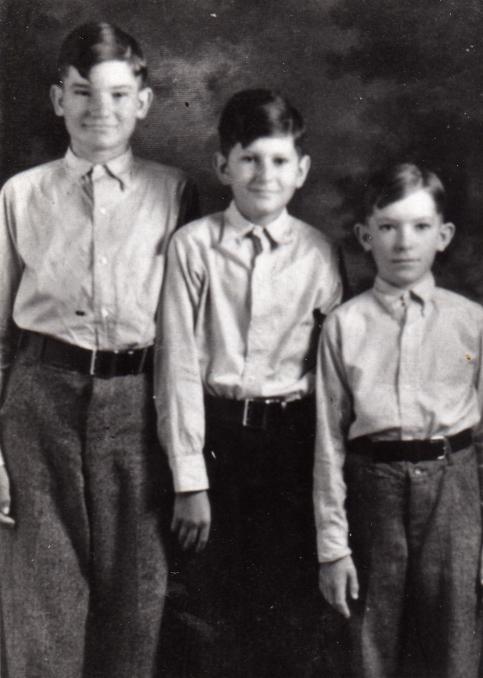

Uncle Marvin, my dad Grady Pierson and Julian (Duke)were brothers my mother Frances and Marjorie Kirkley were sisters, they all courted around together, my mother dated Monroe Wise, before her sister dated him and later Marjorie and Monroe married.

Uncle Marvin had took a job and aunt Marjorie couldn’t find him, when he came back she had already married Monroe, Marvin had hoped to marry Marjorie himself, although she married Monroe she still loved Marvin deeply.

Aunt Marjorie told me she would of left Monroe if she could of found Marvin in time, but the bus she was on was late and heart broken Marvin had left for the war, he was stationed on the U.S.S Jarvis a battle ship, she said she would write Marvin letters daily, sometimes more than one letter and send him pictures and talk of being back together when he returned.

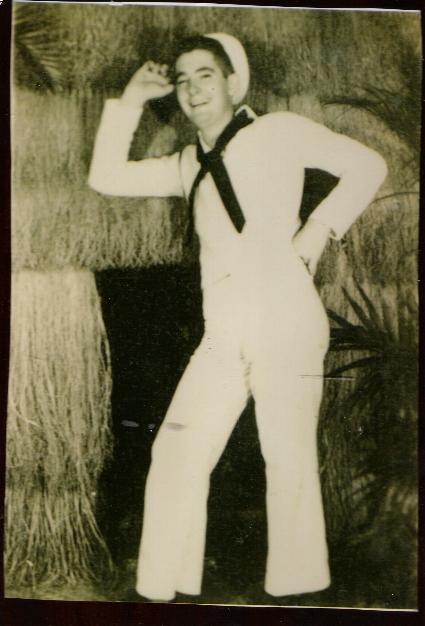

Uncle Marvin wrote her many love letters and send her pictures of himself, he’d put into the envelope with his own hands, she still has a picture she had enlarged of him in his white sailor uniform, he stood so tall and handsome.

Aunt Marjorie was a voluptuous beautiful young woman with blue eyes and golden curls with a stature of 5 feet 2 inches, was the baby of eleven children, her brother Lewis was killed by two drunks, while her mother was carrying her during her pregnancy.

Aunt Marjorie collected many letters and pictures of Uncle Marvin and would hide them from uncle Monroe. He knew she loved Marvin and he was so jealous of her beauty. They separated for awhile, but were back together when she got word from my dad Grady Pierson that Marvin’s ship the U.S.S. Jarvis had been torpedoed and sunk with no survivors, her heart fell and she was so heart sick and cried so in her room, Uncle Monroe said, “so your boy friend’s ship sunk and he’s dead,” but her love to this day has never died, Aunt Marjorie Moore is now seventy four year’s old, with graying hair and a cripple leg from a fall, she uses a walking cane to get around my house, I care for her and my mother Frances Pierson.

My dad has been dead now around a year and a half from Alzheimer’s, I still have my son Jonathan living with us helping as much as he can running errors for mom, Aunt Marjorie and me, as I work at Mother Frances Hospital in the nursery as a unit secretary, this is my twentieth year now doing the orders and feeding the orders in to the computer system.

I’ve heard many stories as mom and aunt Marjorie talk and go over old times, they sat in their chairs in the living room last night speaking of Uncle Marvin and the letters she’d write and pictures she’d sent him went down with the U.S.S. Jarvis ship at sea, It surely upset my aunt as she spoke of the things she’d say and he’d say in their letters to each other.

One letter was while she baby sat with my brother David as a baby, she said in the letter how beautiful he was with his black curly hair and greenish blue eyes were like Marvin’s how sweet David was and he’d cry and when she’d pick him up in her arms he’d stop crying and Uncle Marvin would write back and say that he would stop crying too, if her arm’s were around him, she loved Marvin so much.

She said that granny Pierson didn’t want Marvin to marry her, that granny would pray that he wouldn’t marry Marjorie when he would return home and he never did return home as his ship was lost at sea. My aunt would ask my mom Frances, why did granny Pierson hate her so, what did she have against her, she was just a young girl so in love with Marvin and he in love with her, why did she pray like she did for him not to marry her. She prayed wrong you know, she did and she lost her son.

Grandmother Pierson had became a preacher, she ministered and preached about Jesus and salvation to all who listened and prayed for the sick. My grand father knew when Marvin told him he’d joined the Marines that he’d never see Marvin again, He had sensed that Uncle Marvin would die in the war and he grieved over his going away and so did my grandmother.

My grandmother died when Jonathan and Justin were babies, she died from strokes. She and grandpa Pierson raised seven children my dad was the oldest son, then Julian and Marvin, the girl’s were Barnett, Edna, Ima and Myrtle Dean Olsen who is a nurse for Dr. Sloan here in Tyler, Texas.

Edna and Oscar Craft had seven children, Clifton , Oscar, Noble, Ronnie, Marvin, Virginia and Beatrice. Barnett and Jack Harris had three children: Howard, Clifford and Mary Harris. Clifford Harris who was the fire Chief at Rusk, Texas died during duty fighting a fire, he had a very large funeral many people honored him.

Ima and Jack Brown had two children James and Dorothy, Myrtle Dean and Garden Olsen had one son Fred Brashfield. Grady and Frances Pierson had two children David Earl and Mary June Pierson which is me Mary J. Bowers. Julian and Maxine Pierson had two children: Carolyn and Patricia Pierson. Julian married again and had four children with Elistine: Julie, Mike, Timmy and Karen Pierson .

My mother and dad were the Last of their family to see Marvin alive, they sent him off to sea on the U.S.S. Jarvis Battle Ship that was lost at sea when it was torpedoed by the enemy.

In order: Aunt Marjorie and Aunt Bonnie when young, Aunt Marjorie with Sheba, the Pierson brothers: Grady (daddy), Julian, and Marvin.

As a child in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s, I remember hearing about my father’s youngest brother, Clifford Marvin Pierson, leaving home in 1940 to see the world. He was only seventeen years old when he joined the U.S. Navy in late 1939. As a matter of fact his mother, my grandmother Pierson, had to sign for him according to his sister, my Aunt Myrtle Dean Olson.

My father and mother say they are the last ones in the immediate family to see him alive, as they took him to the bus station where he got transportation to his induction station.

He never returned home.

He was lost at sea near the Islands of Guadalcanal and Savo, which are part of the Solomon Island group, in the South Pacific, near Australia.

I had been told by my parents that his ship was crippled during combat with the Japanese in the South Pacific. They understood that it was sunk by a torpedo discharged from a submarine as it was limping along, headed toward Australia in hopes of being repaired.

My grandparents received notification that his ship, the destroyer. “S.S. Jarvis,” had been sunk and all hands (about 230) apparently had perished. The only tokens they received from the Navy were a purple heart and the few medals and ribbons that he earned during his short career with the U.S. Navy.

Looking back, I remember seeing the purple heart on the wall of my grandparents’ home at 2815 Chandler Road in Tyler, Texas, and hearing that my grandmother, especially, took the news of her youngest son’s death very hard. Years passed before she overcame her grief.

As the years passed, I rarely thought of my uncle as I never knew him. As I said before, he left East Texas before I was born and never returned.

However, one generally begins to appreciate his heritage more and more as the years slip by; and in the last few years I have begun to do some genealogical research along with my wife, Melba.

Several years ago (December 1986) while in Washington, D.C., I was able to find the census record of 1910, which revealed that my grandfather’s father, was born in Georgia in 1853 and his wife, Lemuel, my great-grandmother, was born in Georgia in 1863. Unfortunately, I have not been able to make certain ancestral connections prior to those dates though I have researched several libraries in Texas, Georgia and Tennessee.

In the summer of 1992 I was in Hawaii while visiting the Pacific area as part of my duty with the U.S. Air Force Reserve. While there I visited Pearl Harbor and the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial as well as other exhibits. I noticed the exhibit which depicted the location of all the ships which were berthed in the harbor on December 7, 1941. One of the ships was the” S.S. Jarvis.” Naturally that piqued my interest.

The Jarvis was only about 3,000 feet from the battleship U.S.S. Arizona and about 700 feet from the Minelayer, U.S.S. Oglala when the attack began. Both of these ships were sunk. Over 1,100 sailors who went down with the Arizona and are forever entombed in the ship as she rests where she settled on December 7, 1941, it was a sobering moment.

Through a Naval Reserve friend of mine. Jerry Riddle, Captain USNR, I found out how to contact the Naval Archives Repository. I did so twice via telephone and received several promises to mail me information on the “Jarvis.” These promises failed to materialize, however.

Later in May of 1993, while touring Central America, I was in Honduras at Soto Cano Air Base, where the U.S. Army and Air Force train Reservists and support the Commander-in-Chief of Southern Command, a four star Army General (At that time it was George Joulwan, whom I had met a year earlier in Panama he later became Supreme Allied Commander, Europe.)

I stayed in a “hootch” for a couple of nights and in it there were several magazines, one which advertised that they could provide information on any ship that ever sailed for the U. S. Navy. The magazine was called “Seaweed.” Naturally, I was excited that maybe, finally, I could get some official information on the “Jarvis.” So I sent for and received a short history of the ship along with a couple of pictures.

In essence, it said the ship was commissioned in October 1937, and sailed into Pearl Harbor on 4 December,1941, after participating in exercises near Maui Island. Following the attack by the Japanese the crew went to General Quarters. Within minutes they began returning fire and claimed four enemy aircraft shot down. None of the crew was lost during the attack.

In the months after the bombing at pearl Harbor the “Jarvis” performed escort duty, protecting and escorting convoys between Brisbane, Australia, and Hawaii. Finally, she was called by Admiral Nimitz, a native Texan, to participate in the invasion of Guadalcanal. This was the first American offensive action in the Pacific following the Pearl Harbor attack. The earlier battles of Coral sea and Midway Island, through victories, were defensive struggles.

This first amphibious operation of the war began at 6:50 A.M., 7 August, 1942, with the “Jarvis” participating. After helping protect and screen the unloading transport ships during the day, the “Jarvis” performed night patrol off the southern end of Savo Island.

The “Jarvis” returned to protect further unloading of transports the next day and was attacked, along with other U.S. ships, by Japanese planes. Seventeen of the enemy planes were shot down , but one of them crashed against the right side of the “Jarvis” near the forward fire room and she was stopped dead in the water with a fifty-foot gash in her side.

The world Book Encyclopedia says the campaign for Guadalcanal from 7 August to February, 1943, was one of the most vicious of World War 2.

In addition to the short history received from “Seaweed,” I noticed a book in a Walden Bookstore in San Antonio, about the Guadalcanal Campaign and convinced Melba to buy it for me as a Christmas present. It has additional details about the “Jarvis.”

Both sources agree that the ship was commanded by Lt. Commander W.W. Graham, a young Naval Officer in his mid thirties. He decided to steam to Sidney, Australia, in hopes of receiving repairs. However, the Japanese mistook her for a cruiser and sent thirty-one planes from Rabaul, New Britain, to finish the job.

This happened after the Battle of Savo Island, the most humiliating defeat for the U.S. Navy in World War 2, according to the author of Guadalcanal, Richard B. Frank. He said on the second day of the battle, “Plane after Plane pan caked or cart wheeled into the sea and one “Betty” (a Japanese torpedo plane) succeeded in putting a torpedo into the right side of the “Jarvis,” killing fifteen men and causing severe damage.” He says a “Betty” burst into the superstructure “Hull” on orders from the Fleet Commander. (note-these accounts conflict as to whether a plane or a torpedo caused the initial damage to the “Jarvis.”)

Admiral Mikawa the Japanese fleet Commander sent out scout planes to search for American ships. They mistakenly identified the “Jarvis” as a cruiser.

This was the reason he made such an effort to scuttle her. The “Jarvis’ was limping out of the battle zone as previously noted desperately seeking help. She remained mute, probably because her radios had been destroyed in the earlier air attack.

One Japanese ship, the Furutaka, unsuccessfully fired torpedoes at the “Jarvis” just before 2:00 A.M.

Another Japanese ship, the Yunagi, pulled out of formation and unsuccessfully fired additional torpedoes at the “Jarvis.” After finding her tougher than expected even though seriously damaged, the Yunagi went to look for prey elsewhere.

The “Jarvis” disappeared without a trace, and only after the war did the world know of her last moments.

The Japs reported her end to U.S. Naval historian.

She was reported as a cruiser by the 4th Air Group. Admiral Yamada, Commander of the 25th Air Flotilla, decided to sink the “Man of War.” (after she was identified as a battleship) rather the transport.

Shortly after noon torpedo planes attacked the “Jarvis” and sank her but not before she clawed down two planes and damaged four others. Some men probably survived; but since Commander Graham had jettisoned all boats and rafts after the initial attack, hoping to lighten the load, the men had little chance of survival-through they may have drifted in unfriendly sea under a remorseless sun before being overcome by delirium and, eventually, death. According to Japanese accounts, the “Jarvis” split in two and sank at 1:00 P.M. on 9 August.

The “Seaweed” report says all hands went down, but Frank reports that wounded men were transferred from the ship after the initial attack on 8 August, 1942.

My goal at this time is to see that the name of my Uncle, Clifford Marvin Pierson, is engraved on the wall in the Punch Bowl Cemetery and to find and talk to at least one of the six survivors who were removed from the “Jarvis” after the attack on 8 August, 1942. After the removal of these six men, there remained about 230 men. All of these men were lost at sea about 130 miles Southwest of Savo Island.

The difference in this loss and that of the Alamo one hundred and six years before is only the final number. Both cases there were no survivors. On the “Jarvis” there were about fifty more patriotic American men than there were who defended the Alamo in 1836. They too paid the ultimate sacrifice for their country.

My Nineteen-year-old-Clifford Marvin Pierson-was one of those who paid the ultimate sacrifice.

Thanks, Uncle Marvin, for doing your duty as you knew how! May God bless your memory.

Epilogue to the Story of Clifford Marvin Pierson and the “U.S.S. Jarvis”

Yesterday I received a letter form Senator Graham, U.S. Senator from Texas, with information from the American Battle Monuments Commission. The letter from the Army Colonel in charge of operations (Colonel William E. Ryan) talked about my Uncle Marvin and my classmate Dennis Graham, classmate from A&M. The essence of the matter is that Marvin is recognized on the “Tablets of the Missing” at the American Cemetery in Manila, Republic of the Philippines. Colonel Ryan also promised to send pictures of the sections of the Tablets depicting both Marvin and Dennis’s names within twelve weeks.

In addition he sent along an application form whereby the next of kin can request a memorial marker, with appropriate inscriptions, from the government at no cost, except installation charges. By this letter I’m sending copies of all the information to my father, C.G. Pierson, and Uncle Marvin’s two living sisters, aunts Myrtle Dean Olson and Edna Craft as well as my cousin Oscar Craft (aunt Edna’s second son) and requesting that they let me know which monument they would prefer and where it should be placed.

Most likely it should be installed in the cemetery where Grandfather and Grandmother Pierson and other relatives are buried. I think it would be nice to have a ceremony after the monument is received with as many of the Pierson’s kin attending as possible. The gathering of the clan should take place either on the anniversary of Marvin’s death, August 9 or Memorial Day in 1995.

I’ll be in contact in the near future concerning this issue. Please let me know what your thoughts are.

Colonel Ryan sent additional information Concerning the “S.S. Jarvis” that will be of interest to Marvin’s kin. You’ll see that the ship was named after a young lad who was born in the state of New York in 1787 and died in 1800 fighting with the U.S. Frigate “Constellation.” Thus he was only 13 years old when killed.

There were three ships named Jarvis with Marvin’s being the second (DD-393). A picture of the ship is included in the material received. The story told in the enclosed material is substantially the same that has already been relayed to you all in previous correspondence.

Additional Epilogue to The Story of Clifford Marvin Pierson and the “S.S, Jarvis” (1994 September)

In his work on Guadalcanal, Samuel Elliot Morrison wrote:

For those who were there, or whose friends were there, Guadalcanal is not a name but an emotion, recalling desperate fights in the air, furious night naval battles, frantic work at supply or construction, savage fighting in sodden jungle, nights broken by screaming bombs and deafening explosions of naval shells. Sometimes I dream of a great battle monument on Guadalcanal; a granite monolith on which the names of all who fell and of all the ships that rest in iron Bottom Sound may be carved. At others times I feel that the jagged cone of Savo Island, forever brooding over the blood thickened waters of the Sound, is the monument to the men and ships who here rolled back the enemy tide.”

A monument, indeed, was erected on the island nearly half a century after the Campaign to honor the men who fought there. Unfortunately, few to whom it would mean much will ever get to see it, because of the distance involved.

James Michener wrote, immediately after the war:

They will live a long time, those men of the South Pacific. They had an American Quality. They, like their victories, will be remembered as long as our generation lives, After that, like the men of the Confederacy, they will become strangers. Longer and Longer shadows will obscure them, until their Guadalcanal sounds distant on the ear like Shiloh and Valley Forge.

Quite simply, Guadalcanal was the literal turning point of the war in the Pacific. To paraphrase Richard Frank, “Guadalcanal already sounds distant to the ear, and distance is limited, but immortality is unlimited.” God Bless

David E. Pierson August 1994

Cc; C.G. Pierson, Edna Craft, Myrtle Olsen, Oscar Craft

Above pics are 1. The USS Jarvis and 2. Uncle Marvin

Many thanks to all who come to recognize one of our own who left East Texas many years ago and gave his all in service to his country. I would especially like to thank Mr. Jim Ferguson and the members of the local chapter of the VFW who have come to help in this service. Also to be commended are the Naval reserve Color Guard unit who have or will present the colors.

Of course all of his kinfolk who are here must be thanked for taking time to remember a young kinsman who left home and hearth in 1941 and never returned. In particular his brother, my father, Charles Grady Pierson and his sisters, Edna Craft, and Myrtle Dean Olson should be recognized.

The Holy Scripture says, ”life is but a vapor that appears for a little while and then vanishes away.”

Philosophers, theologians, great thinkers and common folk, in quite moments, ponder the brevity of life. Even the three score and ten years allotted to mankind, according to the Bible, is but a flicker in the mind of the Almighty God for whom a thousand years is but a day.

The one who we have gathered together to recognize today was with us for less than twenty brief years. Clifford Marvin Pierson’s flame flickered only nineteen years, six months and twenty nine days before it was snuffed out at about 1:00 O’clock P.M. on August 9, 1942-fifty-three years ago last Wednesday.

Marvin served aboard the U.S.S. Jarvis, a U.S. Navy Destroyer as seaman First Class. His was berthed in Pearl Harbor on that, “Day of Infamy,” December 7, 1941, during the attack by Japanese warplanes the crew claimed the downing of four enemy planes without sustaining any damage.

After the attack the Jarvis provided protection for transports and supply ships plying the waters between Hawaii and Australia for several months. In mid July 1942 the Jarvis received a assault on Guadalcanal. Thus began the first American Offensive action in the Pacific Theater of World War 2. The mission of the Jarvis was to protect the Marines as they stormed the shores and proceeded to capture as airfield being constructed by the enemy. The airfield was later named Henderson Field.

Marvin’s ship was the first U.S. ship struck by Jap torpedo planes at the beginning of this gruesome, vicious six month campaign which was the beginning of the road to the devastation of the evil Japanese Empire. On August 9, 1945, exactly three years after the sinking of the Jarvis, the last Atomic bomb to be used in warfare was dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, killing over 60,000 human begins. Many were vaporized instantaneously, others died months and years later.

The Jarvis sustained a huge gash over fifty feet long and was stopped dead in the water when struck by the torpedo. All communications were lost and several casualties were inflicted on the crew. After receiving temporary repairs the skipper, Lieutenant Commander Graham, decided to steam toward Australia, from whence she had been berthed upon receipt of the secret order from Nimitz, in hopes of getting permanent repairs. Many orders fly back and forth in the “Fog of War.” Apparently Graham failed to receive the order sent from Fleet Admiral Turner to sail to an Island in the Solomon chain for further repairs. With the damage received, and confusion, however, it is understandable that this could happen. The skipper also ordered all life rafts and other gear tossed over board in effort to keep the ship afloat. These life rafts might have saved some of the crew had they been available when the final attack occurred.

Nevertheless, while limping toward Australia the Jarvis was identified as a heavy cruiser by Jap scout planes and the Jap Fleet Commander, Admiral Mikawa, sent gig teen torpedo planes escorted by sixteen zeros to eliminate what they thought was a capitol ship. Shed was blown out of the water, as noted before, at 1:00 O’clock on August 9, 1942.

After the initial dust settled from this, the opening salvo of a six month campaign, an intensive air and sea search was begun to find the Jarvis. No clue whatsoever was ever found and the Jarvis was listed as the “Destroyer that vanished” in the records of the U.S. Navy. Six weeks later the next of kin were notified that all hands, 230 in all were missing in action. My grandparents, Jim Hogg and Monnie V. Pierson, were among the recipients of this disturbing news.

In 1950 an article appeared in the “United States Naval Proceedings” written by Commander James C. Shaw telling the story of the Jarvis” last moments. After the surrender of the Japanese, interviews with authorities and review of the records enabled Navy historians to piece together the final moments of the Jarvis and her crew. Otherwise we would never have known what happened to them.

All of us who knew or were kin to Marvin appreciate very much your participation in this belated ceremony more than fifty years after the incident. Because of the delay in receiving official notice of his death a memorial service was never held prior to today, At long last, however, we dedicate the plaque which was placed in his memory next the grave of his parents. I want to show all of you the wall displays with medals and purple heart. These were made in the honor of the finest young men who ever graced East Texas.

Furthermore, let me end by reminding you that the only difference in the service of those aboard the Jarvis in 1942 and those who served in the Alamo in 1836 was the number who died. At the Alamo about 180 died and on the Jarvis 230 died. In both cases the men who served gave their all in defense of their country.

God bless my uncle Marvin for making the Ultimate Sacrifice. He Did His Duty As He Knew How.

David E. Pierson, COL (Ret) USAFR.

Pics are: Marvin's memorial service with David and Melba Pierson in center, Aunt Mirtle Dean holding Marvin's memorial plaques.