BACK TO THE FAMILY OF

FOUR

A little later in the same day after I was told about the crash, the

F.A.A. told us that the pilot of the plane had probably wandered into

cloudy zero visibility

conditions for which he was not certified to fly, and he flew it into

the side of an 11,000 foot mountain east of San Bernardino.

But what about that mistake I made during the job?

The Piper Cherokee 180 came into our facility for a 100 hour inspection

including servicing the engine with a leak down compression check, oil

and filter change and dual magneto synchronization checks in addition

to other visual inspections and aircraft documentation checks. It

was a Saturday, so I was working alone for the day.

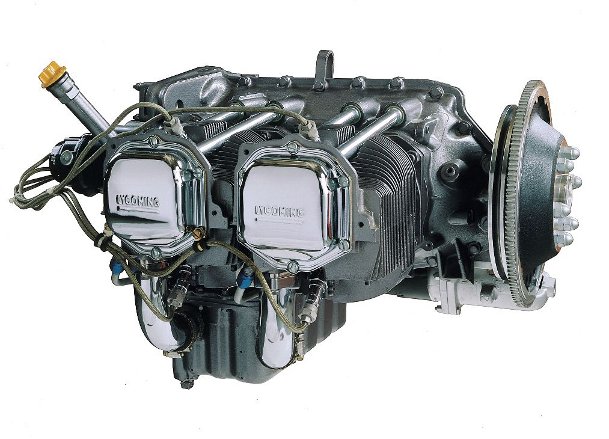

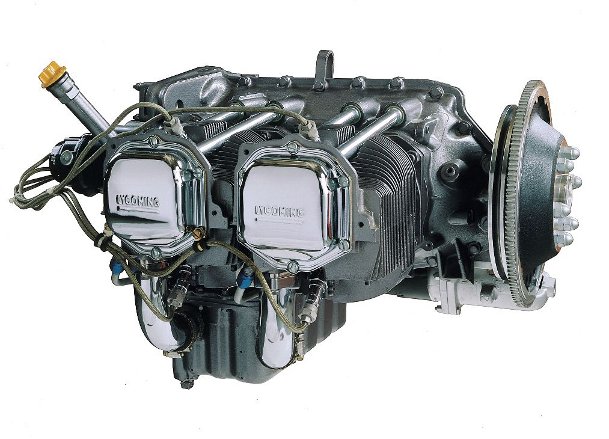

The engine was an Avco Lycoming 0-360 A4A, a 360 cubic inch

displacement four cylinder opposed air cooled piston engine of 180

horsepower, naturally aspirated and carbureted. Nothing fancy,

very simple with 8 spark plugs and two magneto ignition systems. (Ironically,

seven years later I would become an aircraft accident investigator

employed by Lycoming.)

While changing the oil in the engine, I had just

replaced the oil filter. Then the phone rang in the hangar and I

answered it. That led to some running around and a little

momentary confusion. When I got

back to the airplane, I finished some other tasks, then started up

the engine for leak tests. About 30 to 40 seconds later I noticed

it! Horror overcame me and I shut down the

engine.

No oil pressure. I had forgotten to put oil in the engine.

My first error was neglecting to put oil in the engine. My second

error was not fixing my eyes on the oil pressure gauge on engine start

like I always do. I thought about

it for a minute, and then I decided that since I had just drained the

oil about an hour prior and it had only run 30 seconds, it was probably

not damaged. "What a dummy!" I thought to myself. No

strange noises came out of it at the time. So I finished the

service, tied up some loose

ends, took the airplane out to the runup area and tested the engine

coming up with normal results in all parameters. I signed off

the airframe and engine logbooks and released

the aircraft for service. I went home, coming back to work to the

bad news.

Even though later in the day we'd gotten a hint of the possibility that

the pilot had probably flown into the side of a mountain while in the

clouds, I lived for 4 days in misery. On the fourth day, the FAA

informed our facility that the accident was a CFIT (controlled flight

into terrain) accident with the engine operating at full 100 percent

climb power setting when it impacted the side of the mountain and that

no mechanical issues were involved.

I had dodged a bullet.

The pilot was probably climbing through a cloud layer in zero

visibility conditions and never even saw the mountain coming at him and

his family. It's easy to do. You can think that the cloud

layer is thin and you'll only be in it for 10 or 20 seconds to pop out

of the top of the layer. This guy must have gone into the

underside of the layer and that was it. Unreal.

I

was not at fault, the pilot was. The FAA and NTSB never even

interviewed me, not once. I haven't thought about that in

a long time. In fact, up until I started looking into some of the

subject matter for this writing, I can't think of the last time I had

ever thought about it. I must have wanted to forget it.

About three years later I made another mistake that cost 100 thousand

dollars in a corporate aircraft turbine engine test fire that was very

much my fault. More about that later.

Now we'll look at some experiences with the MEDA investigation approach.

PAGE FIVE: Experiences with the MEDA Process

BACK to TM page one